New results on multi-agent active perception at NeurIPS 2020

We have a new paper entitled “Multi-agent active perception with prediction rewards” at the 34th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2020). The paper is also up on arXiv. This is research done together with Frans A. Oliehoek.

Summary

We propose a reduction from a Dec-POMDP with a convex information reward to a standard Dec-POMDP. Now all standard Dec-POMDP algorithms are applicable to multi-agent active perception problems, and we can solve larger scale problems.

In more detail

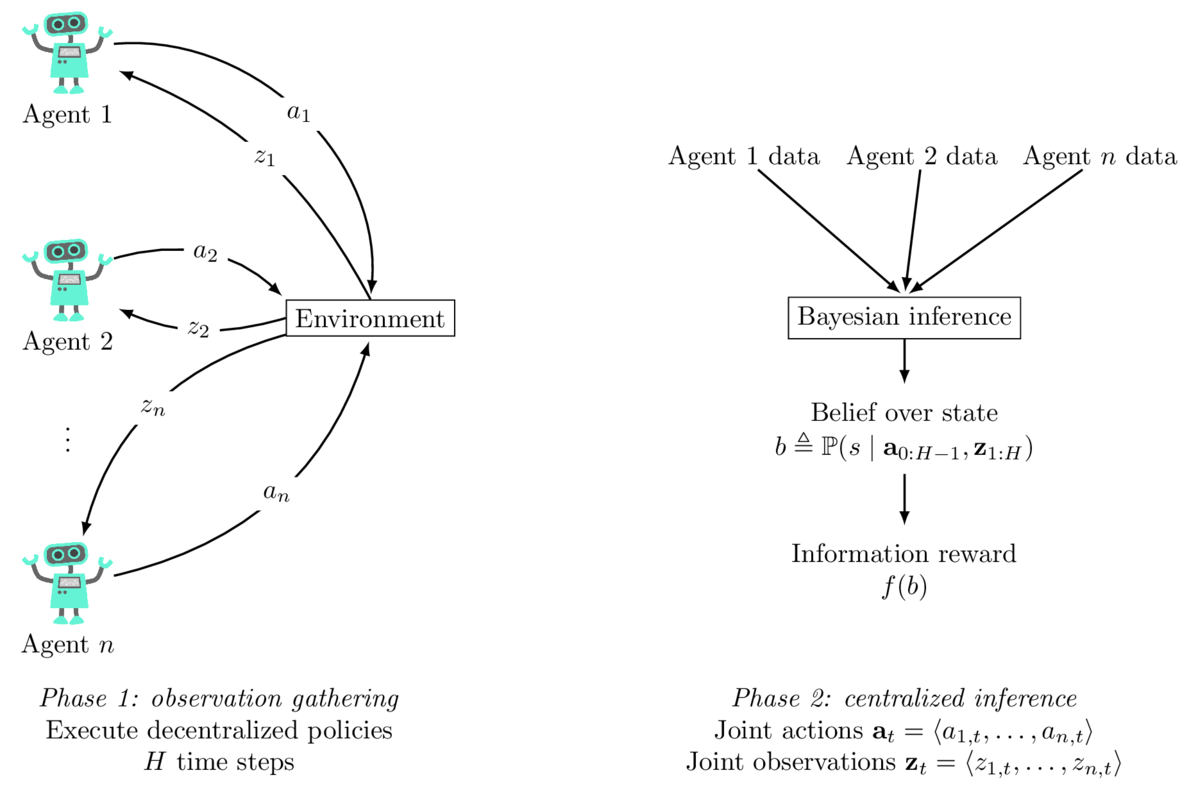

The setting of the paper is illustrated in the figure below. The multi-agent active perception problem consists of two phases: the decentralized observation gathering phase (left) where agents act independently based on their private information, and the centralized inference phase (right) after the end of the task, where a belief state is computed and the agents are rewarded according to the informativeness of the belief state. A solution is a set of individual policies, one for each of the agents, that an agent can execute in a decentralized manner. At the end of the task after a finite number of time steps, the observations collected by the agents are collected at a central server for inference. This enables computation of a state estimate, or belief state, and the overall reward of the agent team is determined by the informativeness of the state estimate, measured for instance by the negative entropy. This type of problem formulation could be applied to settings like search and rescue robotics, multi-robot environment monitoring missions, or distributed sensor networks.

This problem can be modelled as a decentralized partially observable Markov decision process (Dec-POMDP) with a special kind of information reward, as I did in my earlier work. Because the information reward depends on what the agents know about the state rather than what the state is, most standard algorithms for Dec-POMDPs are not applicable to this problem, and indeed we proposed some specialized algorithms in earlier work to tackle this. However, one of the issues of these algorithms is that to search for policies, we have to compute and store in memory all of the possible state estimates that could be reached during the task. This is very memory intensive, and as a result these algorithms have trouble scaling up.

In the new paper, we address these two issues in a neat way: we propose a conversion of the entire problem into a completely standard form Dec-POMDP, with the typical kind of reward function! This means that all of the standard algorithms for Dec-POMDPs are now applicable to solve multi-agent active perception problems. Modern Dec-POMDP solvers do not need to compute all reachable belief states, but can instead rely on techniques such as Monte Carlo sampling to evaluate and search for policies. Technically, we achieve the conversion by introducing so-called prediction actions, inspired by similar earlier work in centralize control settings. To put things briefly and informally, the prediction actions “decentralize” the state estimation problem in a way that each agent will also make a prediction about the true state at the end of the observation gathering phase.

The conversion we propose induces a loss, but we show that the loss is bounded and that there are cases where the loss is zero. We show experimentally that by our conversion, scalability in the planning horizon is greatly improved compared to previous methods.

I’m also excited about the opportunities for future research the results open up. By linking multi-agent active perception to standard Dec-POMDPs, any advances in one are immediately transferable to the other. Standard Dec-POMDPs are also the most popular underlying formalism for multi-agent reinforcement learning under partial observability, so by this reduction we potentially enable learning for multi-agent active perception. Looking deeper at when the loss due to the conversion is small could further boost the practical applicability of the method.

You can read about the details in the paper, and try out the conversion and a solver algorithm by checking out the code.